Rev 1.1

So what is it about tortillas? Like most civilizations, the mesoamericans ground up a grain and made a cooked meal of it. The nahuatl speakers called it/them - the cooked pieces... "cooked food." Of course after years of calling it this, the word means that bit of food, that round flat piece of bread that one uses to scoop up beans or meat... and the Nahautl word is tlaxcalli. (tlash-cal-li)

Tlaxcalli? So where does the word tortilla (tor-tee-ya) come from? Well, many words from the Nahuatl made their way into other languages, such as avocado and chocolate. In this case the spanish for small round piece of bread took over the nahuatl. A torta in spanish is a piece of bread or cake, mostly round, most of the time. So the Spaniards called these round pieces of flat bread tortas and the Nahautl speakers added on the proper diminutive that the word needed and we end up with the word: tortillas.

Making tortillas was hard work. Before mills, making bread in Europe was hard work; and in both parts of the world it was women's work. Grinding grain is hard, it takes rocks and muscles. Europe, with it's domestic animals, developed grinding stones that were powered by horses, mules, asses or oxen, and women found many other chores to do.

Corn (european for grain), maize (taino for what we call corn), cintli (nahuatl for corn), call it what you will, cannot be ground dried. It has to be processed first.

In Mesoamerica, without the benefit of domestic animals, women ground the grain well into last century, by hand. A large gently curved stone, called a metatl; or, in spanish, metate, rectangular in shape, with three or four little feet that hold one narrow end up higher than the other was the daily taskmaker of most of the women of Mesoamerica. The long cylinder, a little shorter than the narrow width of the metatl, called the mano (hand) was rubbed over the grain pieces sort of like a rolling pin.

(found on the net)

The women knelt in front of the high end of this stone and ground away to make the masa.

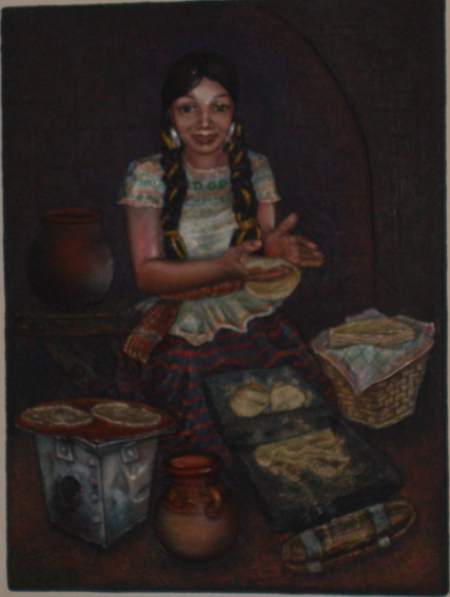

This is a very idealized picture of the tortillera. The work is backbreaking, even (especially) if you've been doing it for forty years. It's tedious, and the women I remember knelt on hard ground or concrete floors. They wore the blusas and voluminous faldas or enaguas and often an apron over that. But what I most remember about their faces as they lined the Coyoacan market aisles or markets in the far flung little villages, was their tiredness. Their hair was neatly braided and tied out of the way and their faces were lined and stressed and strained. Each one trying to judge how many tortillas to make before she sold them, trying not to make too many, and not too few, and hoping to sell them all before the customers stopped coming. And by my time, they were mostly just making the tortillas not grinding the masa as well.

The whole tortilla making process is very complicated, as I will shortly show.

According to Oscar Lewis, when the mill came to Tepoztlan, Morelos, women suddenly had five free hours a day. And the first mill failed because men would not let their wives use the mill; they felt all that free time would be bad for them. It didn't take long for a quiet revolution to take place among the women and the second mill survived. This was all in the early 1900's.

From 1930s I have found authors who say that the sound of México for them is the early morning slapping sound of the tortilleras. Women lined the aisles of the market places, each with their little brazier and comal atop it. Each had her kilo or 2 or 10 of masa and spent the day slapping those tortillas flat and baking them on the flatiron. It's a motion like clapping; right hand over left and left over right, back and forth quickly so the dough does not stick to the hands and rip the tortilla.

By the time I was a child in México in the mid to late 1960's that sound had been mostly replaced, freeing up thousands of women to pursue an education and a wonderful career... like sweeping the streets, embroidering blouses, working in sweat-shops. Does this sound bitter? The truth is, many things are better than kneeling before a metatl grinding for five hours, with a fire going next to you, adding to the heat, and baking tortillas all day while kneeling on a hard concrete floor, with only your skirts bunched up to give you a cushion.

So, what replaced that sound? The squeak and rattle of the early tortilla making machines, with their hoppers, pressers, conveyer belts and jets of propane flames cooking the tortillas. And that squeak and squeal is the sound of México, today.

Here in Zacatecas I found most of the tortillerías are one stop shops. I was used to the tortillería of my childhood receiving the masa from an outside source. The truck would pull up with huge burlap wrapped loads, as big as a man's torso. The man in the shop would run out and get the lump on his back, between the shoulders and stagger back into the hot dark hell of the machine room and dump the masa on a table at the back. The other person there would pay off the driver and they'd grab chunks of masa and feed the hopper.

Having bought all my tortillas in one tortillería (except for the Sunday I could only find the local grocery shop open) I asked if they'd let me photograph the operation. They said yes, come Saturday at 10am.

As you can see, this shop, Tortillería Genaro Cedina, has been in existence a long time. These plaques are mostly painted over on the rest of the shops in the market place, as new renters have moved in and the old ones vanished into history.

Yes, it's as hot as the ones I remember from long ago. Fueled by propane gas, a lot of energy goes into making tortillas. This morning it was relatively cool in there; they'd only started operations.

"So where are my tortillas?" asks the lady. "Right here, ma'am. 1 1/2 kilos, on the dot," says the nice owner, busily pulling tortillas off the machine and sorting them into stacks.

So, the corn, having been planted, protected, cared for and harvested and dried; now comes to this factory in huge sacks of roughly shucked corn kernels.

In the back there is a bag of salt and the white and green bags are calcium phosphate. The grains must be boiled in Calcium Phosphate water to stop them from sprouting. I seem to remember soaking the kernels for 48 hours before boiling and grinding, but they don't pre-soak it. They boil it for about 90 minutes in lime water.

Every tortillería needs a good price list.

The bags of kernels are emptied into that bin (barely visible) on the right. They are full of grains, shucks, bits of cornstalk and cob. A conveyer belt pulls up small amounts which are blown on by the fan at the top and rattled down a screen designed to take out all the small stuff. This falls into the bag at the bottom of the tube (center). The cleaned corn falls into the bin on the left.

This corn is not completely clean, but a lot of the muck has been knocked off or sorted out. Women used to take out their measure of corn on the husk from the family store, shuck it and sort it by hand. Chalk up 30 to 60 minutes depending on how much they were going to make. Each kernel would get a hard finger twist that rubbed off all the residue from the husk.

With this modern method, the cleaned grains are picked up using that five gallon bucket. They are littered all around the operation and seem to serve as an informal kind of measuring cup. I didn't ask, however. Most of the non-edible stuff is now lighter than water, while the grains are heavier. Cleaned grain is dumped into one of two "boiling bins" and calcium phosphate is added. The five large gas flames are lit under the bin and the grain is cooked. All the muck from the cobs and stalks and leaves float to the top and are skimmed off.

The lime water is very important. I was taught that it stopped the corn from sprouting... and so it does. But a horrible human experiment was carried out when corn was exported to Europe and Africa soon after the conquest. Cheap, easy to grow in the right conditions, yielding better than wheat and rye, it quickly became a staple of the poorer segments of many societies. The poor promptly began to suffer from pellagra a disease that led to death in four to five years. Pellagra is a deficiency disease. Unknown to all until the late 19th century, soaking the corn in lime water released the access to niacin and it's predecessors. Once people in the American South, europe and Africa soaked the grain before processing it in lime water the deficiency disease disappeared.

That's not all that's cooking here. The tortillería is a one stop shop for their customers. On the side they boil up huge vats of beans and sauce that they also sell.

A tired housewife going home in the evening, or cleaning woman finishing up at 11am, can wander in here and purchase enough for their families. The beans and sauces are poured into plastic bags which are knotted at the top. Surprisingly they don't spill.

When people are ready to use them they cut the bottom corner off and pour them out without bothering with the mess at the knot.

The cooked grain is bailed out of the boiling bin and dumped into this sink. Here water is added to it and it is rinsed clean of the boiling calcium phosphate water.

The cleaned corn is picked over and ladled into the hopper of the grinding machine. Water is added and the machine starts to chew through the grain.

The masa (dough) falls through to the bin below. The operator watches the quality carefully, sweeping the gobs together and making sure it holds in a clay-like mass. Otherwise, they might put it through again with more water or more grain to balance the quality.

The dough is stored under damp clothes until needed. There was enough dough that I couldn't get a picture of the hopper in operation.

My nice lady has just started the machine. She is rolling up the tortillas that are coming out. The machine isn't properly hot yet and she just pops the soft dough back into the hopper until she feels enough heat to cook them properly.

Ah! Now there is enough heat. And she lets them roll. Only one machine is operating right now. At peak times they have all three going. They generate about a tortilla a second. It takes around 40-60 tortillas to make a kilo. Many customers want four or five kilos. But people like their tortillas piping hot, so they try not to get a backlog.

The soft dough runs down a long flat conveyer belt, that is practically speaking, a flatiron.

At the end of the run, they are stiff enough and half cooked and they plop down onto a chainlink conveyer belt that exposes them to more heat and make their way back up the machine.

Here she opened the safety door so I could photograph the "plop" piece.

Off they come, into a little hopper, so fast the camera couldn't keep the image still. The women working this part of the operation pick them up every minute or so and treat them as we would a sheaf of paper, sorting, shaking and getting them into one neat stack.

Do I miss the slap/slap of the tortilleras and their tired faces? I do not. I like the happy, friendly smily face of this lovely lady and her crew. And the rattle click of the tortilla machines means a good hot tortilla, fresh off the hot machine, rolled around a bit of salt and salsa while I wait patiently for my -Un cuarto, por favor.-